A Guide to Traditional and Modern Painting Methods

by Frederic Taubes

Paints  (p 27)

Modern paint is deficient in one important respect ‚ÄĒ the nature of its body. Otherwise, in point of brilliance, color retention, and variety, the best available modern paints would seem to equal and in many cases surpass those used in the past.

If the old masters succeeded in achieving better and more lasting color effects than many of the painters of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries this must be ascribed partly to their superior knowledge of the craft and partly to the medium they used as a vehicle for their pigments.

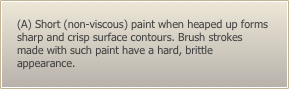

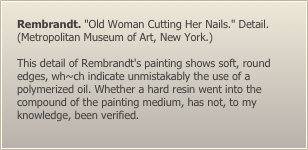

Modern tube paint lacks viscosity, not only because the oil used for binding the pigments is neutral (of low ac Id value) and unpolymerized but because it contains an additive (aluminum steareate) that effectively counteracts the viscous condition.

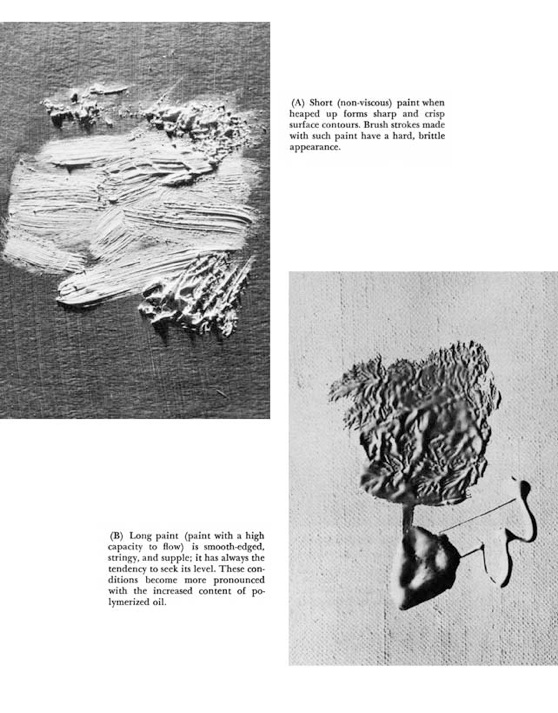

At the same time it allows the pigment to remain in permanent suspension with the oil. Without this stabilizer (or other suitable ingredients), the oil and the pigment would separate, making it impossible to store paint in tubes for indefinite lengths of time. Hence, tube paint is nonviscous, or as we call it, "short." By adding polymerized oil to the paint we can make it viscous, or "long."

Oil Painting Mediums  (p 28)

Taking a cue from the medieval monk Theophilus, who was the first to leave a precise account of the preparation of oils and paints, I have managed to re-establish formulas that were current even before the times of the Van Decks, and that were responsible for the creation of classic paintings of unsurpassed permanence and beauty.

These formulas have now been available for a long time under the name of "Copal Painting Medium" (light and heavy-the first is less viscous than the second), "Copal Concentrate," and "Copal Varnish." They are manufactured by Permanent Pigments, and are generally available in artists'-material stores. However, several different brands of Copal painting mediums are available, but some, because of different composition, may act differently. The media serve, as the term implies, for thinning of the tube paint while painting.

Oil paint, being of dense consistency, often requires considerable dilution by the medium. Sometimes, as in glazing, this consistency may approximate that of watercolor. The concentrate should be added to each of the colors after they have been squeezed from the tubes onto the palette. This oil-and-resin compound changes the brilliance and accelerates the drying of the paint. The medium should not be used for under-painting, because in the lower layers of a painting it serves no useful purpose. However, its use does not prohibit additional overpainting when this is required.

Before the procedures are discussed in detail, it should be stated that linseed oil, the best binder for pigments, is in many respects inadequate as a paint thinner (or medium) because of three principal considerations. First of all, it has low degree of viscosity; second, it fails to attach itself properly to the canvas when mixed with paint to a liquid consistency; and third, it has a tendency to yellow regardless of its quality and the degree of its purification. This tendency becomes more noticeable with extensive use, such as in glazing.

As a binder for pigments linseed oil, as stated before, is perfectly adequate; however, a minimum quantity is used in the average tube paint, because the manufacturer tries to give the painter the maximum amount of pigment. In other words, he cuts down on the oil content. However, there is nothing easier than to mix a painting medium with the tube colors and thus improve the bond of the pigments.

Painters often use turpentine as a thinner, but this is inappropriate. Turpentine destroys the cohesion of the paint film and makes it brittle, and also prevents it from receiving a proper coat of varnish. Another common fault is to mix soft resin such as damar or mastic varnish with the oil paint. The surface of such a painting remains susceptible to damage if treated even with the mildest solvent when the time comes for it to be cleaned. Instead, copal resin should be used to give the painting permanence and resistance to cleaning agents.

The Characteristics of Copal Concentrate  (p 31)

This material, used to make the paint more viscous, is a thick honey-like substance combining copal resin and stand oil. A little of it (the size of a small bean) should be scooped up from the bottle with the palette knife and well mixed with about one inch of each color as it comes from the the advice given already by Theophilus.

Only flake white should receive a considerably larger amount of the substance to make it flow. Whereas all the other colors become more liquid when mixed with the concentrate, white lead, because of a chemical reaction, stiffens when a small amount of concentrate is added.

The more concentrate that is added to the paint, the more the colors will assume the character of enamel; hence the amount used should be regulated according to the painter's requirements. The addition of concentrate makes every color appear more brilliant. After mixing the above, paints are then thinned with the painting medium as desired.

Viscosity of Paints  (p 32)

Viscosity refers to the capacity of a liquid to flow; the less viscous the paint, the more free its flow. This in itself is not the only important quality in a painting medium. Stand oil (depending on the degree of its polymerization) can be extremely viscous, and, in spite of its superior qualities such as non-yellowing and the toughness of its linoxyn, it offers too many limitations to be perfectly satisfactory. Thus in choosing the medium we must consider the viscosity plus the capacity to attach itself to the support (when used thinly) , as well as other working qualities.

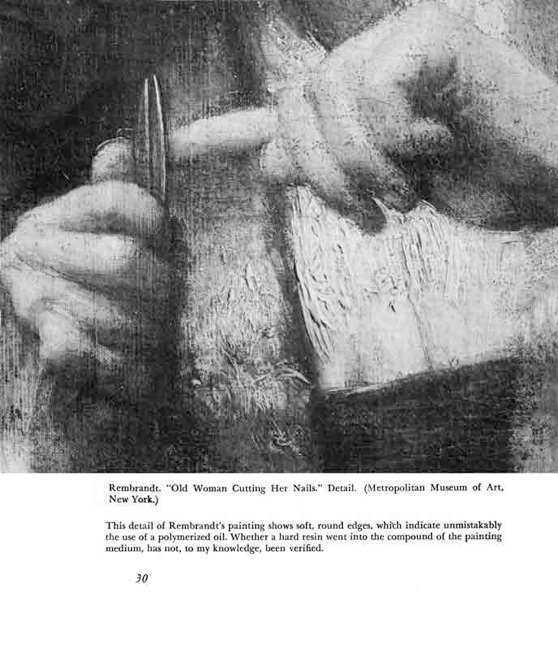

The condition of "attachability" which arises due to the presence of the resin in the medium has already been mentioned. As to the desirability of viscosity, this condition promotes fusion and blending of colors in a manner hardly attainable when working with a dilutent such as the raw linseed oil. Moreover, it allows the painter to work wet-on-wet with ease, superimpose wet applications one on top of the other without churning up the underlying paint strata, and altogether to create effects that are comparable to those of the Flemish masters.

Open Color Painting  (p 123)

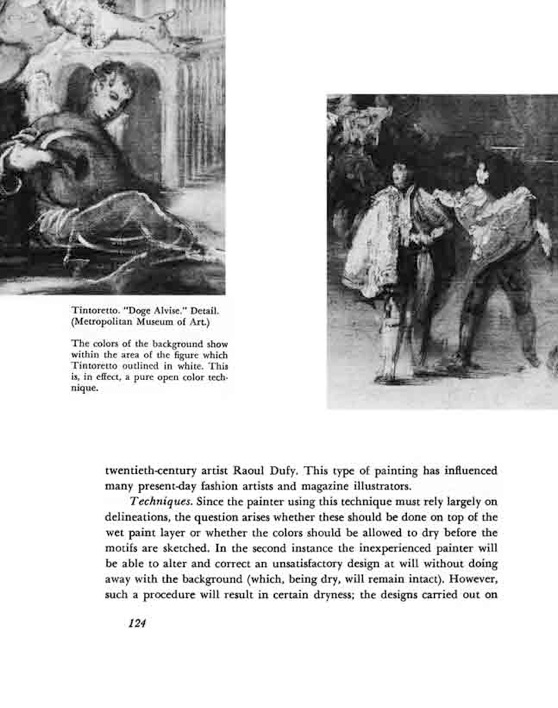

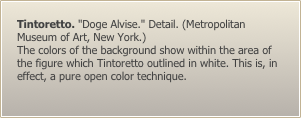

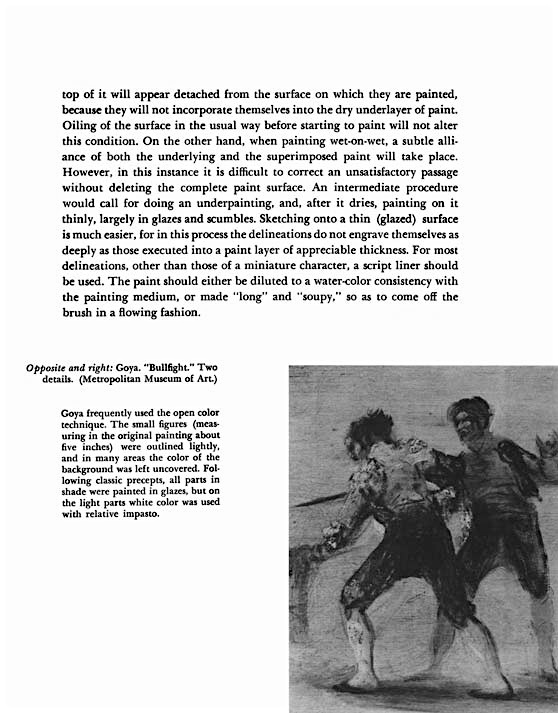

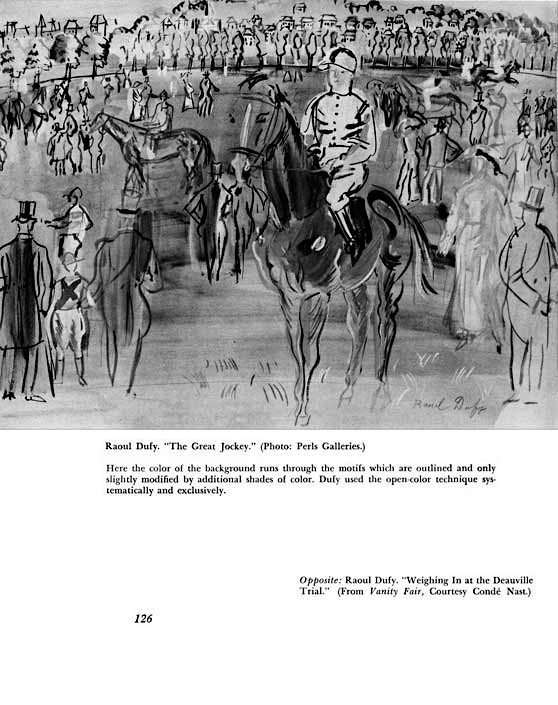

In essence, open color painting constitutes a simplification, comparable to shorthand writing. It reduces painting to drawing with color, relieves the heavy-handedness that sometimes weighs down painting with superfluous details and elaborations, and altogether it allows the painter's hand to express itself by means of linear definitions with speed and freedom. This technique cannot be looked upon as a "style" of painting, for it can enter into almost any mode of pictorialization. Tintoretto was among the earliest painters to use it although the method may have been known much earlier. Examples of the open color technique are seen in the details reproduced from a painting by Goya, and in the painting by the twentieth-century artist Raoul Dufy. This type of painting has influenced many present-day fashion artists and magazine illustrators.

Since the painter using this technique must rely largely on delineations, the question arises whether these should be done on top of the wet paint layer or whether the colors should be allowed to dry before the motifs are sketched. In the second instance the inexperienced painter will be able to alter and correct an unsatisfactory design at will without doing away with the background (which, being dry, will remain intact). However, such a procedure will result in certain dryness; the designs carried out on top of it will appear detached from the surface on which they are painted, because they will not incorporate themselves into the dry underlayer of paint. Oiling of the surface in the usual way before starting to paint will not alter this condition. On the other hand, when painting wet-on-wet, a subtle alliance of both the underlying and the superimposed paint will take place. However, in this instance it is difficult to correct an unsatisfactory passage without deleting the complete paint surface. An intermediate procedure would call for doing an underpainting, and, after it dries, painting on it thinly, largely in glazes and scumbles. Sketching onto a thin (glazed) surface is much easier, for in this process the delineations do not engrave themselves as deeply as those executed into a paint layer of appreciable thickness. For most delineations, other than those of a miniature character, a script liner should be used. The paint should either be diluted to a water-color consistency with the painting medium, or made "long" and "soupy," so as to come off the brush in a flowing fashion.

read

Book Excerpt

below

The Frederic Taubes Gallery                            phone 203-894-8930                        Info@FredericTaubes.com