В

В

В

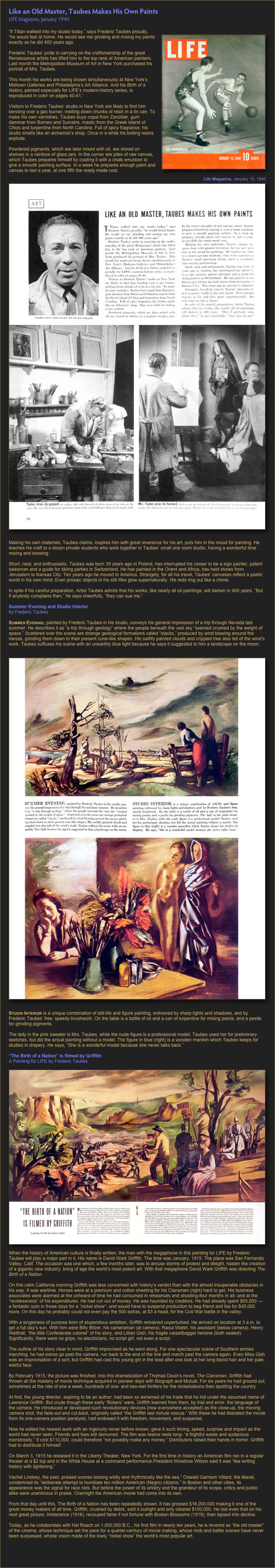

In this January

1940В issue,

LIFE Magazine published a profile of Frederic Taubes and his work

The Frederic Taubes GallerYВ В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В В Info@FredericTaubes.com

В

В