Â

Â

Â

Frederic

Taubes

On Crafts-

manship

Text-only

Version

Â

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

10.

crafts-

manship

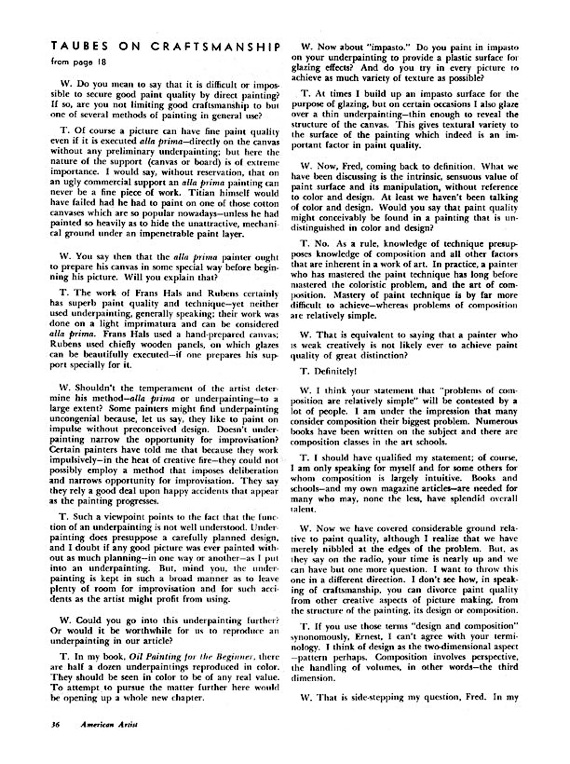

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

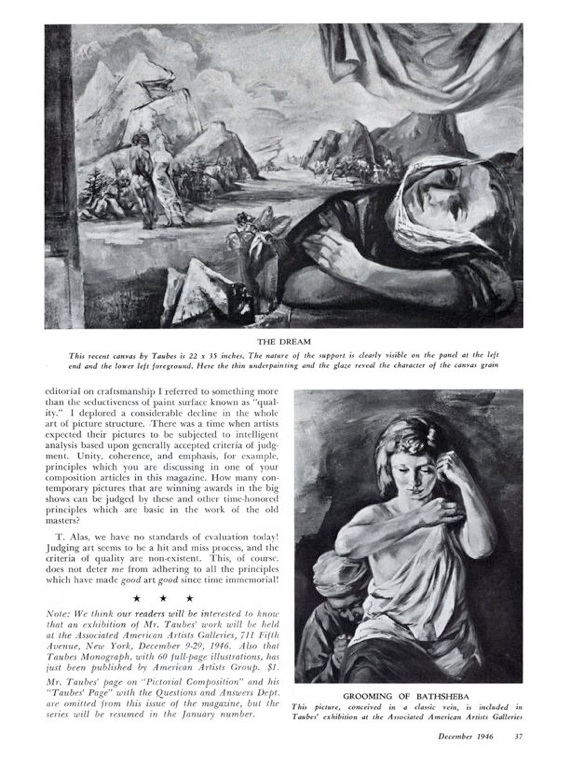

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The Frederic Taubes GallerYÂ Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Info@FredericTaubes.com

Â

Â