9.

retro-spective

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

The

Page

The text of this article is reprinted at the bottom of the page

American

Artist

Magazine

The Taubes Page

![Frederic Taubes: A Retrospective

By Diane Casella Hines

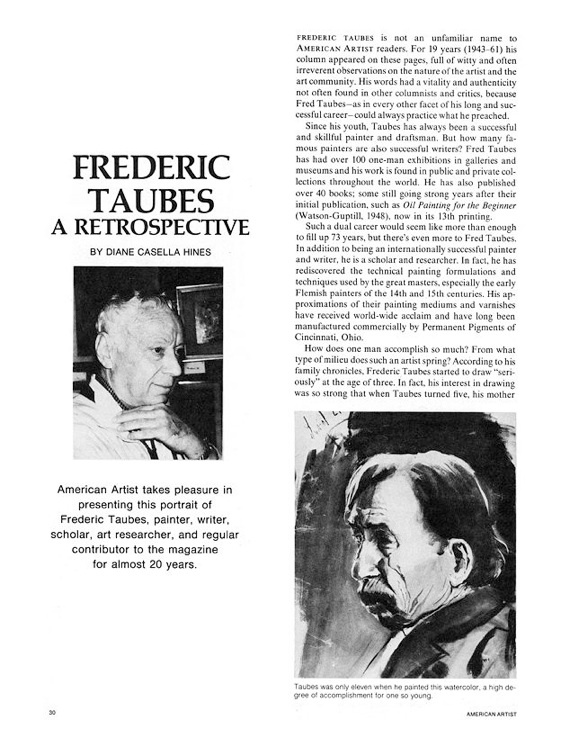

American Artist takes pleasure in presenting this portrait of Frederic Taubes, painter, writer, scholar, art researcher, and regular contributor to the magazine for almost 20 years.

FREDERIC TAUBES is not an unfamiliar name to AMERICAN ARTIST readers. For 19 years (1943-61) his column appeared on these pages, full of witty and often irreverent observations on the nature of the artist and the art community. His words had a vitality and authenticity not often found in other columnists and critics, because Fred Taubes-as in every other facet of his long and successful career- could always practice what he preached.

Since his youth, Taubes has always been a successful and skillful painter and draftsman. But how many famous painters are also successful writers? Fred Taubes has had over 100 one-man exhibitions in galleries and museums and his work is found in public and private collections throughout the world. He has also published over 40 books; some still going strong years after their initial publication, such as Oil Painting for the Beginner (Watson-Guptill, 1948), now in its 13th printing.

Caption:

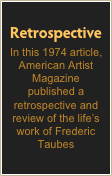

Taubes was only eleven when he painted this watercolor, a high degree of accomplishment for one so young.

Such a dual career would seem like more than enough to fill up 73 years, but there's even more to Fred Taubes. In addition to being an internationally successful painter and writer, he is a scholar and researcher.

In fact, he has rediscovered the technical painting formulations and techniques used by the great masters, especially the early Flemish painters of the 14th and 15th centuries. His approximations of their painting mediums and varnishes have received world-wide acclaim and have long been manufactured commercially by Permanent Pigments of Cincinnati, Ohio.

How does one man accomplish so much? From what type of milieu does such an artist spring? According to his family chronicles, Frederic Taubes started to draw "seriously" at the age of three. In fact, his interest in drawing was so strong that when Taubes turned five, his mother engaged an artist to tutor the child privately.

At that time the Taubes family was living in Lvov, which was then the capital of Poland, a province of the Austrian Empire. Taubes's art instruction continued for the next nine years, and he attended classes with some of the city's finest painters. The watercolor of a Polish peasant (reproduced here) was created by Taubes at age eleven.

Taubes's life took on its peripatetic style in the summer of 1914. That year his home town came under siege by the Russians. Fortunately, his family was abroad on summer holiday; unable to return to their home, the Taubes family moved to Vienna.

For the next four years the teenage Taubes spent countless hours in the Imperial Museum of Art and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. In fact, he was more often at these places than in high school, where the only subject that interested him was Latin.

This language seemed to offer a pathway back to the past, which fascinated Taubes. Especially exciting to him at this age were the paintings of the Old Masters, especially the Flemish. Taubes longed, even at this age, to uncover their "secrets" and create the "magic" that he felt they had captured in their work.

When World War I ended, Taubes moved to Munich and entered the Academy of Fine Arts and the studio of Max Doerner, who was then the foremost expert in painting technology and methods of the Masters. With Doerner, Taubes thought that all the mysteries the paintings of the Old Masters represented would be revealed to him. But this was not to be.

After about a year, Taubes became disenchanted with his studies at the Academy. He left and traveled to Weimar, where he entered the newly established Bauhaus, the first official academy of Nonobjective Art.

This bit of personal history might seem surprising to those who associate the Taubes name with such scathing critiques of modern art as those found in his books You Don't Know What You Like and Modern Art: Sweet and Sour. (It was the critical success of You Don't Know What You Like (published in 1942) that prompted Ernest Watson‚ÄĒwho with Arthur Guptill founded American Artist‚ÄĒto invite Taubes to come to the magazine as a regular writer.

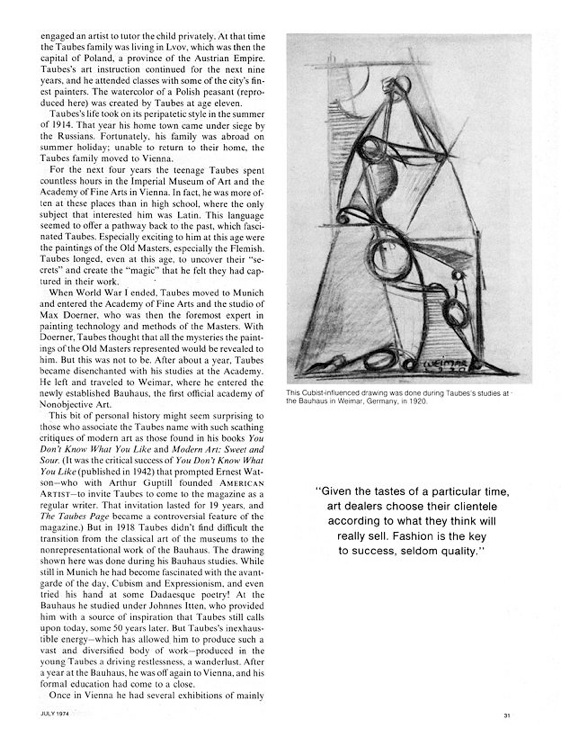

That invitation lasted for 19 years, and The Taubes Page became a controversial feature of the magazine.) But in 1918 Taubes didn't find difficult the transition from the classical art of the museums to the nonrepresentational work of the Bauhaus. The drawing shown here was done during his Bauhaus studies.

Caption: This Cubist-influenced drawing was done during Taubes's studies at the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany, in 1920.

"Given the tastes of a particular time, art dealers choose their clientele according to what they think will really sell. Fashion is the key to success, seldom quality."

While still in Munich he had become fascinated with the avant-garde of the day, Cubism and Expressionism, and even tried his hand at some Dadaesque poetry! At the Bauhaus he studied under Johnnes Itten, who provided him with a source of inspiration that Taubes still calls upon today, some 50 years later. But Taubes's inexhaustible energy which has allowed, him to produce such a vast and diversified body of work-produced in the young Taubes a driving restlessness, a wanderlust. After a year at the Bauhaus, he was off again to Vienna, and his formal education had come to a close.

Once in Vienna he had several exhibitions of mainly avant-garde, abstract work that gave him a certain notoriety in art circles. At this very period a catastrophic inflation was sweeping post-War Austria, and the Taubes family, along with the rest of the nation, found itself in bad financial straits.

By this time Taubes was married, and with the birth of his son he had to seek ways to earn a steady income. In quick succession he became a poster painter, skiing instructor in the Swiss Alps, and finally a newspaper artist- reporter. This last job, though taken out of necessity, proved to be the starting point for the resumption of Taubes's career as an artist.

At that time the reproduction of photography had not yet been perfected, and newspapers needed drawings of people and events. Taubes was soon assigned by a local newspaper to write feature articles and sketch various visiting dignitaries and celebrities. Such work led him to a five-year stint as a portrait painter.

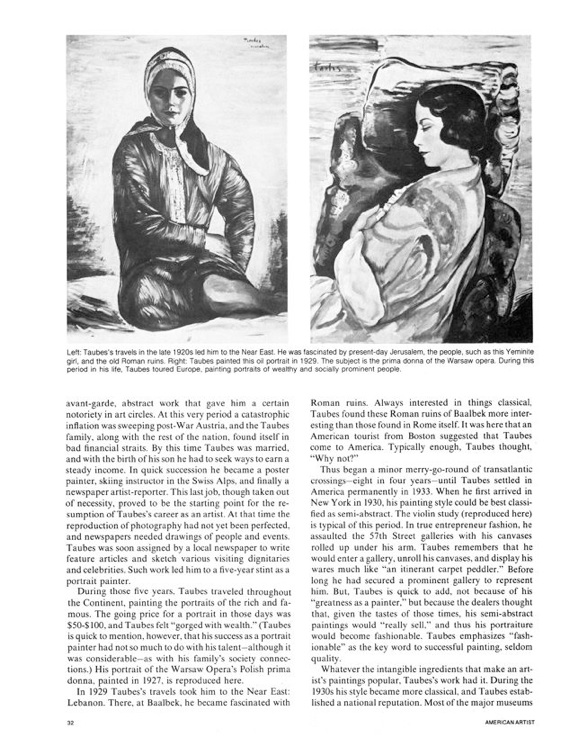

Caption Left:

Taubes's travels in the late 1920s led him to the Near East. He was fascinated by present-day Jerusalem, the people, such as this Yeminite girl, and the old Roman ruins.

Caption Right:

Taubes painted this oil portrait in 1929. The subject is the prima donna of the Warsaw opera. During this period in his life, Taubes toured Europe, painting portraits of wealthy and socially prominent people.

During those five years, Taubes traveled throughout the Continent, painting the portraits of the rich and famous. The going price for a portrait in those days was $50-$ 100, and Taubes felt "gorged with wealth."

(Taubes is quick to mention, however, that his success as a portrait painter had not so much to do with his talent-although it was considerable-as with his family's society connections.) His portrait of the Warsaw Opera's Polish prima donna, painted in 1927, is reproduced here.

In 1929 Taubes's travels took him to the Near East: Lebanon. There, at Baalbek, he became fascinated with Roman ruins. Always interested in things classical., Taubes found these Roman ruins of Baalbek more interesting than those found in Rome itself. It was here that an American tourist from Boston suggested that Taubes come to America. Typically enough, Taubes thought, "Why not?"

Thus began a minor merry-go-round of transatlantic crossings-eight in four years-until Taubes settled in America permanently in 1933. When he first arrived in New York in 1930, his painting style could be best classified as semi-abstract. The violin study (reproduced here) is typical of this period. In true entrepreneur fashion, he assaulted the 57th Street galleries with his canvases rolled up under his arm.

Taubes remembers that he would enter a gallery, unroll his canvases, and display his wares much like "an itinerant carpet peddler." Before long he had secured a prominent gallery to represent him. But, Taubes is quick to add, not because of his "greatness as a painter," but because the dealers thought that, given the tastes of those times, his semi-abstract paintings would "really sell," and thus his portraiture would become fashionable. Taubes emphasizes "fashionable" as the key word to successful painting, seldom quality.

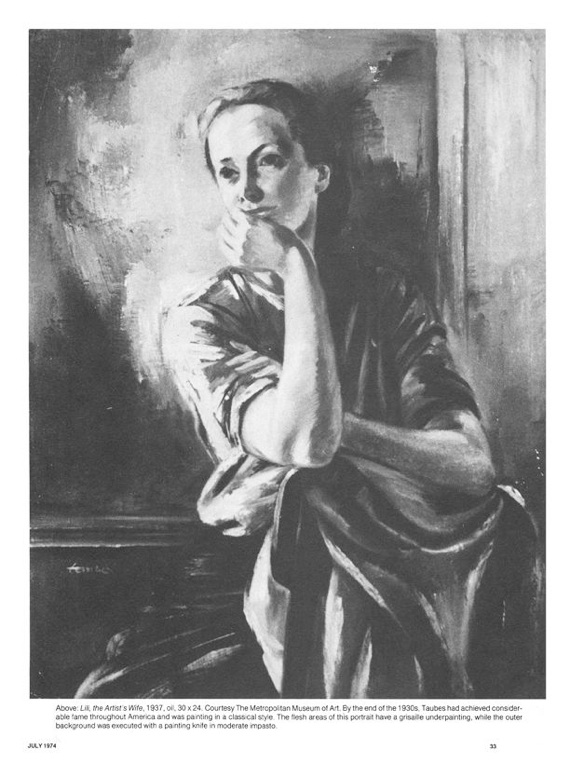

Caption Above:

Lili, the Artist's Wife, 1937, oil, 30 x 24. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. By the end of the 1930s, Taubes had achieved considerable fame throughout America and was painting in a classical style. The flesh areas of this portrait have a grisaille underpainting, while the outer background was executed with a painting knife in moderate impasto.

Whatever the intangible ingredients that make an artist's paintings popular, Taubes's work had it. During the 1930s his style became more classical, and Taubes established a national reputation. Most of the major museums in America "had to have a Taubes." (Lili, a 1937 portrait of the artist's wife, is owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

At the same time, Taubes was invited to teach and lecture at scores of colleges in the United States and abroad. He conducted dozens of classes a year in all parts of the country, including The Art Students League in New York.

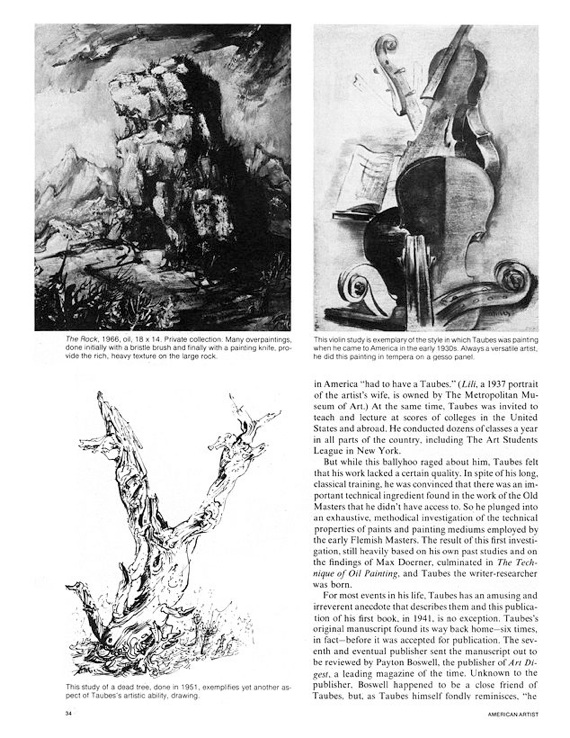

Caption:

The Rock, 1966, oil, 18 x 14. Private collection

Many overpaintings, done initially with a bristle brush and finally with a painting knife, provide the rich, heavy texture on the large rock.

Caption:

This violin study is exemplary of the style in which Taubes was painting when he came to America in the early 1930s. Always a versatile artist, he did this painting in tempera on a gesso panel.

But while this ballyhoo raged about him, Taubes felt that his work lacked a certain quality. In spite of his long, classical training, he was convinced that there was an important technical ingredient found in the work of the Old Masters that he didn't have access to. So he plunged into an exhaustive, methodical investigation of the technical properties of paints and painting mediums employed by the early Flemish Masters.

The result of this first investigation, still heavily based on his own past studies and on the findings of Max Doerner, culminated in The Technique of Oil Painting, and Taubes the writer-researcher was born.

Caption:

This study of a dead tree, done in 1951, exemplifies yet another aspect of Taubes's artistic ability, drawing.

For most events in his life, Taubes has an amusing and irreverent anecdote that describes them and this publication of his first book, in 1941, is no exception. Taubes's original manuscript found its way back home-six times, in fact-before it was accepted for publication. The seventh and eventual publisher sent the manuscript out to be reviewed by Payton Boswell, the publisher of Art Digest,, a leading magazine of the time.

Unknown to the publisher, Boswell happened to be a close friend of Taubes, but, as Taubes himself fondly reminisces, "he [Boswell] knew just a bit less about the technical aspects of oil painting than he did about animal husbandry." But Boswell's report to the publisher was glowing.

In Taubes's experience both the art world and the world of publishing seemed to be governed by almost every factor except an adherence and attention to the true worth and merit of their respective products. But in the case of The Technique of Oil Painting, Mr. Boswell's report proved true: the book went through 17 revised editions in America and half as many in England. The editions were revised because, shortly after the book's publication in 1941, Taubes was forced to begin repudiating the book's form, due to his new and quite startling finds.

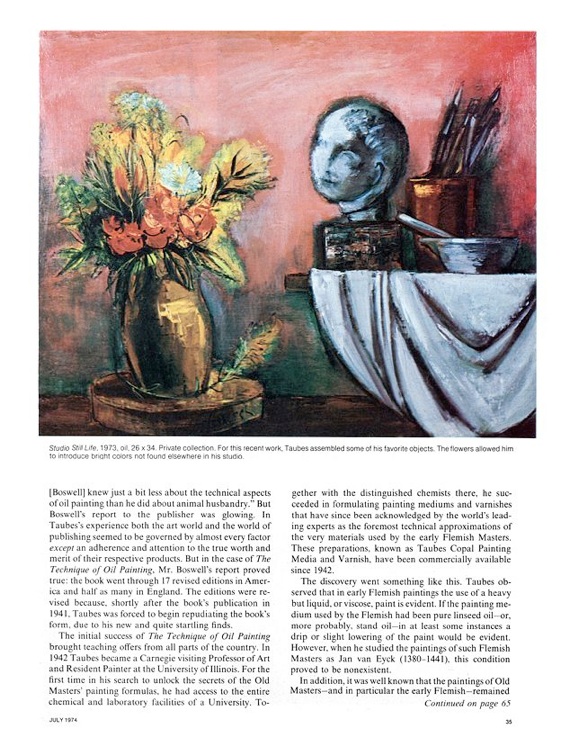

Caption:

Studio Still Life, 1973, oil, 26 x 34. Private collection.

For this recent work, Taubes assembled some of his favorite objects. The flowers allowed him to introduce bright colors not found elsewhere in his studio.

The initial success of The Technique of Oil Painting brought teaching offers from all parts of the country. In 1942 Taubes became a Carnegie visiting Professor of Art and Resident Painter at the University of Illinois. For the first time in his search to unlock the secrets of the Old Masters' painting formulas, he had access to the entire chemical and laboratory facilities of a University.

Together with the distinguished chemists there, he succeeded in formulating painting mediums and varnishes that have since been acknowledged by the world's leading experts as the foremost technical approximations of the very materials used by the early Flemish Masters. These preparations, known as Taubes Copal Painting Media and Varnish, have been commercially available since 1942.

The discovery went something like this. Taubes observed that in early Flemish paintings the use of a heavy but liquid, or viscose, paint is evident. If the painting medium used by the Flemish had been pure linseed oil-or, more probably, stand oil-in at least some instances a drip or slight lowering of the paint would be evident. However, when he studied the paintings of such Flemish Masters as Jan van Eyck (1380-1441), this condition proved to be nonexistent.

In addition, it was well known that the paintings of Old Masters-and in particular the early Flemish-remained practically undamaged after cleaning with the most powerful solvents, including acetone. Taubes had a hunch that the missing, or undiscovered, ingredient in the composition of the paint or painting mediums of these artists might be a hard resin.

Why a hard resin? Why not a soft resin like damar or mastic, which have always been used up to modern times? The key was the impervious quality of these paintings. Years after completion and cleaning with strong solvents, they still remained intact. Soft resins, such as damar, are dissolved even by a mild solvent, such as mineral spirits.

The most common hard resin found in nature is "Congo copal," so called because it was originally found in underground deposits in what was once the Belgian Congo. Such a hard resin requires high- temperature heating to make it compatible (soluble) with oil.

Taubes discovered that both the deposits and the thermal processing of the Copal were known in the days of the early Flemish painters. In a manuscript written by a 12th century monk, Theophilus, there is a distinction made between hard and soft resins, and a recipe is given for thermally processing the resin. Though primitive, this recipe describes the essentials of a process that is still in use today.

About this same time in 1942, the research of Dr. Paul Coremans, director of the Laboratoire Central des Mus6es de Belgique in Brussels, confirmed Taubes's hunch. Dr. Coremans and his staff were working on the restoration of van Eyck's Ghent Altar. Using microchemical studies of cross-sections of its paint layers, Coremans concluded that van Eyck's medium contained a substance showing characteristics of a natural resin.

To further support Taubes's assumption that this resin was a hard one, Coremans established that turpentine (an important solvent for resin varnishes) existed in Europe at a much earlier time than was previously thought (1345-1346). Coremans himself verified this earlier arrival of turpentine with findings that he uncovered in research at the archives at Bruges.

Taubes journeyed to Brussels in 1952 to consult with Coremans personally about his hard resin theory. In 1953 Taubes published his findings concerning hard resins and the painting mediums of the Masters in The Mastery of Oil Painting, which was hailed by experts throughout the world and is still in print today.

The publication of this book in England brought Taubes an invitation to lecture at Oxford and the Royal College of Art. As mentioned earlier, Taubes's approximations of these Old Masters mediums are commercially available today.

If we could enter Fred Taubes's studio today and watch him work, what painting techniques would we see him using? Following the example set by the Old Masters, Taubes generally uses the technique of underpainting when working in oils.

First, he always prepares his canvases himself. After he has stretched the canvas, he covers its surface with gellified (not liquid) glue, which serves to size it. Then, depending on whether the texture of the canvas is coarse or smooth, he primes his canvases with one to three coats of white lead. To this white lead he often adds just a touch of umber oil paint. This paint helps to speed up the drying time of the white lead.

Meanwhile, Taubes nails down the correct composition of his painting with a drawing that he usually executes on tracing paper. When the charcoal drawing finally suits him, he transfers it to his primed canvas.

Now Taubes is ready for his underpainting. With this underpainting he blocks in the main features of his composition in "understated" colors. These paints contain a large amount of white lead. The following colors are all that Taubes needs in any first underpainting: ochre for yellows, umber and Prussian blues for grays, Venetian red for pinks, and umber for brownish grays.

Depending on the nature of his painting's subject matter, he will apply a second and possibly a third underpainting. These underpaintings serve to enrich color and create impasto and other textural qualities.

When his underpaintings have dried thoroughly (which usually takes a few days), he is ready to apply his final overpainting. But before doing so, he covers all the areas on the underpainting that will have overpainting with the Copal Medium. "Oiling" in this fashion reduces friction between the brush and the painted surface and increases the luminosity of his colors.

Taubes rubs the Copal Painting Medium into the underpainting with a stiff brush or his finger. He removes any surplus medium with a lint-free cloth or a flexible, rather sharp-edged knife. Applied in this manner, only the thinnest film of painting medium remains. He also mixes a little "Copal Concentrate" into every one of his oil paints.

This compound, also formulated from Taubes's discoveries, contains stand oil and Copal resin. It changes the body of tube oil paints, which are essentially "short" (stiff and sticky) and makes them "long," or more viscous. It also enhances the color of the paints. Thus, such oil paints more closely approximate the viscous mediums used by the Old Masters.

As for varnishing, Taubes uses retouching varnish shortly after his painting is complete to revamp "sunk-in" colors. About a year after the painting's completion, he applies his Copal Varnish. A week or so later, he revarnishes the entire painting with damar picture varnish.

If such a protected painting becomes dirty in ten or a hundred years, the layer of dirt can be removed with solvents, and the film of the old Copal Varnish will remain intact, protecting the original condition of the painting.

The greatest virtue of this underpainting technique is its flexibility. Such a procedure -rather than impeding an artist's spontaneity, as devotees of the alla prima method might claim-allows for the maturing of artistic concept. It permits the artist more time to work out the details of his initial inspiration.

Any profile of Taubes would not be complete if his important research into methods of restoring antiques-especially statuary-were not mentioned. In fact, a method of restoring damaged objects made of marble that Taubes pioneered (first described in Restoring and Preserving Antiques, Watson-Guptill, 1969) was used in repairs made recently on Michelangelo's Pielb.

After 73 years of artistic accomplishment, countless paintings, publication of over ' 40 books, innumerable awards, and production of approximations of the Old Masters' painting mediums, you would think that Fred Taubes would retire to his studio, among his own superb collection of antique statuary, and relax-or at least slow down. But not so. That restless, surging energy that invigorated him as a young man has only slightly decreased with age.

This spring Clarkson N. Potter will publish Taubes's 41st book: The Human Body, Aspects of Pictorial Anatomy. Taubes's trenchant observations of the foibles of the art community are still issuing forth each month on the pages of The Artist. The world has not yet seen the last Taubes's painting and certainly has not heard his last word. And most assuredly, Frederic Taubes, an art legend in his own time, will have that last word.](Frederic_Taubes_Archive___American_Artist_-_A_Retrospective_files/shapeimage_12.png)

The Frederic Taubes GallerY                    Info@FredericTaubes.com